Due to her own contradictory stories and the sensationalism of the late 1950s media, Adeline Watkins is still one of the more sinister myths surrounding the Ed Gein story. Watkins stepped forward to claim a decades-long romance after Gein was caught after a graphic disclosure of his crimes, depicting a picture of peaceful friendship entwined with grisly admissions. She talked about how they would spend evenings talking about books and “every murder that we ever heard about.” She also acknowledged that Gein had previously asked her to marry him, but she had declined because she was afraid she would never be able to live up to his expectations.

In part because Watkins set their bond at twenty years, this first story sparked a surge of public interest. However, a few weeks later, she mostly withdrew that assertion in an interview with a local newspaper, claiming that her previous version was “blown up out of proportion” and that the actual duration of their liaison was, at most, less than a year. She explained that although they had known one another for twenty years, they didn’t start communicating more frequently until 1954. Her public identity as a romantic figure, confessor, or untrustworthy storyteller was confounded by her about-face.

Adeline Watkins — Biographical Profile

| Field | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Adeline Watkins |

| Approximate Birth Year | circa 1907 |

| Age in 1957 | ~50 years |

| Residence | Plainfield, Wisconsin |

| Known Relationship | Claimed romantic link with Ed Gein |

| Duration of Claim | First claimed 20 years, then retracted to under a year |

| Public Statements | “Good and kind and sweet” (earlier), later said claims were exaggerated |

| Involvement in Crimes | No evidence supports her complicity in Gein’s crimes |

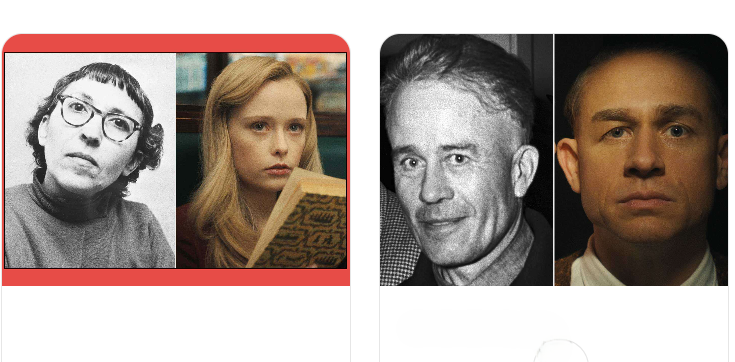

| Portrayal in Media | Character in Monster: The Ed Gein Story series |

| Source Reference | Interviews in Minneapolis Tribune, Stevens Point Journal |

Watkins is immersed in Gein’s criminal world in the Netflix series Monster: The Ed Gein Story; she shares his fetishistic images, takes pictures of corpses, and becomes a confidante in grave robbery. Historians and true-crime experts warn that there is no reliable archival or testimonial evidence to justify such levels of engagement, despite the fact that it is compelling for dramatic effect. Gein himself never publicly acknowledged her, and no forensic documents link her to the physical crimes.

The conflict between media amplification and personal remembrance is seen in Watkins’ two disparate interviews. Her words captured fetid curiosity and filled newspapers in the first recounting. She appeared to shed a lot of the glitz in the second, recasting herself as a supporting character rather than the main conspirator. Her fluctuating story reminds me of how memory may become pliable when it is influenced by stress and attention.

Despite the sensationalization of Watkins’ accusations, her personality comes to light—not as a villain, but as a complex lady facing strange celebrity. Although her portrayal of Gein as “sweet” and “kind” stands in stark contrast to the horrifying things he did, her own retraction implies the difficulty of reconciling that contradiction. She may have done so out of remorse, fear for her safety, or a wish to remain anonymous in the face of fame.

Adeline Watkins is a prime example of how ancillary characters surrounding notorious criminals are incorporated into mythology among true-crime viewers. The public’s desire for coherence in horror events, sensationalism, and reinterpretation have all influenced Watkins’ narrative, much to how Anna Sorokin (the “Fake Heiress”) became a part of Anna Delvey lore or how Patty Hearst’s story was altered over the course of decades.

Two decades after Gein’s death, and over seventy years since Watkins’ interviews, her fate remains mostly unrecorded. She was born about 1907, and if she were still alive, she would be far over 110 years old, making survival improbable. Her life after the retraction era is not confirmed by any subsequent public records. Therefore, those old newspaper pieces and fictional reinterpretations hold a large part of her legacy.

The distinction between reality and fantasy becomes increasingly significant as Monster expands its audience. Viewers are prompted by Watkins’ portrayal to consider the proportion of the story that is grounded in archive truth and the proportion that is dramatic flourish. Although she is portrayed in the series as a psychological co-conspirator, there is no evidence of this in the historical record. Instead, she occupies the uncomfortable liminal area between character and witness, serving as a warning about the morality of true-crime reporting.