The bond between Olu Dara and his son Nas is remarkably unusual for anyone following the beating heart of contemporary society through its musical origins. In addition to showing how music changes over time, it also demonstrates how powerfully it may influence public opinion in ways that go well beyond mere amusement.

Charles Jones III, better known as Olu Dara, never sought popularity. Rather, he developed a life influenced by the Mississippi blues and the inventive improvisation of the jazz scene in New York. His music struck a deep chord with musicians who valued ambiance over algorithm and tone above trend. His son was born with that subtle elegance—not by force, but by a presence that hung in the air like brass following a solo.

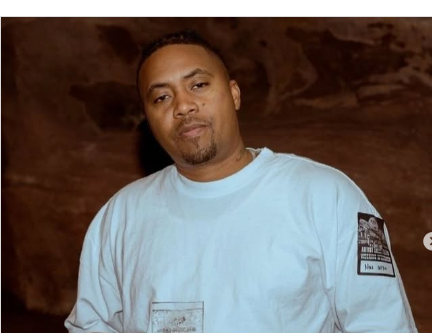

Profile Summary: Olu Dara’s Son – Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones |

| Stage Name | Nas |

| Date of Birth | September 14, 1973 |

| Place of Birth | Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Father | Olu Dara (Charles Jones III), jazz/blues musician |

| Notable Family Members | Jungle (brother), Yara & Sayeed Shahidi, Tracy Morgan (cousins) |

| Career Start | 1989, under the name “Nasty Nas” |

| Landmark Album | Illmatic (1994), inducted into the National Recording Registry |

| Major Label Deals | Columbia, Def Jam, Mass Appeal Records |

| Grammy Recognition | Best Rap Album for King’s Disease (2020) |

| Known For | Lyrical storytelling, cultural influence, social consciousness |

Nasir Jones, who grew up in the Queensbridge housing projects after being born in Brooklyn, was exposed to that environment at a young age. He started penning lyrics that sounded like prophecies and read like poetry by the time he was a teenager. His bars held a beat that had been passed down from his father but had been altered by a far harsher reality. Nas’s debut album, Illmatic, which he released at the age of 20, is still regarded as one of the most emotionally charged, lyrically ambitious, and structurally sound works of hip-hop.

It was more than just a solo record. Olu Dara provided a brief but remarkably clear cornet solo on the song “Life’s a Bitch.” It was a moment so understated that it might have gone unnoticed by casual listeners. But that one flash of brass created a sound connection between father and son. Olu Dara not only backed Nas’s debut with the feature, but he also gave it a legacy. It was mentoring by contribution rather than by teaching.

Nas has not only maintained its relevance over the last thirty years, but has also continuously changed it. As American discussions about racism, poverty, power, and identity have changed, so too has his narrative. He has reflected public struggle through his own history in especially creative ways. Songs like “One Mic,” “I Gave You Power,” and “Daughters” reveal a musician who is really interested in the consequences of men losing their sense of direction and how music may bridge that gap.

By the early 2000s, Nas and fellow New York rapper Jay-Z were involved in a well-known and tense spat. Particularly in songs like “Ether,” which displayed Nas’s keen wit and ability to counterpunch with style, the rivalry was laced with lyrical precision. It was a defining and explosive time. But like most great artists, introspection was followed by reconciliation. After some time, the two reconciled, and Nas joined Def Jam during Jay-Z’s presidency. It was a full-circle moment, similar to the shaking hands of jazz and rap.

Nas’s career path has significantly improved over the last ten years, particularly when he entered the media and business industries. Nas has proved especially helpful to young creatives looking for alternatives to traditional gatekeepers as a co-founder of Mass Appeal Records and an investor of several tech firms. His strategic yet audacious business decisions have increased his impact without compromising his integrity.

Nas has demonstrated that lyrical brilliance and financial acumen don’t have to coexist by forming strategic alliances to invest in real estate, cryptocurrency platforms, and streaming services. He has accomplished this with a subtle elegance that is comparable to his father’s jazz playing in that it is nuanced, deliberate, and spotlight-free. There is no denying Olu Dara’s impact here.

The fact that Nas has always been an artist first and foremost is what gives his journey such versatility. He continues to put out albums that are well received by both fans and critics despite his decades of fame. King’s Disease, King’s Disease II, and King’s Disease III, his most recent trilogy, which Hit-Boy produced, is a masterwork of late-career resuscitation. In addition to winning him his long-awaited Grammy, the first installment demonstrated that, when done well, storytelling never goes out of style.

Nas has increased the scope of his societal contributions in recent years. Distant Relatives, his 2010 joint collaboration with Damian Marley, explored African identity and legacy; all proceeds went to support educational and developmental projects throughout the continent. Olu Dara’s early fascination in cultural fusion and diasporic sound was mirrored in this uncommon record, which was immensely melodic but activist in spirit.

Their partnership speaks volumes within a larger cultural context. In a time when musical legacies between fathers and sons are sometimes boiled down to superficial parallels, Olu Dara and Nas stand for something very resilient. Their story is about growing while being grounded, not about imitation or nostalgia. Not just what Nas has accomplished, but also how closely it is linked to his origins, is what makes his story so emotionally captivating.

Few families have been able to maintain their creative relevance in a variety of musical genres. The Coles performed in soul and jazz. The Dylans combined rock and folk music. However, the Dara-Jones legacy fills in one of the greatest misunderstandings: the gap between the rapid pace of hip-hop and the reflective quiet of jazz. Instead of producing dissonance, that contrast has enhanced the stories of both artists.

Nas has accumulated 17 studio albums since the 1994 release of his debut album, many of which have received gold or platinum certifications. More tellingly, his lyrics are ingrained in the DNA of up-and-coming musicians throughout the business, examined at academic institutions, and cited in films. Nas is cited by Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, and Joey Bada$$ as both an inspiration and a model.

Olu Dara, on the other hand, is still involved in a few jazz circles and plays when the occasion demands it, never out of duty. Despite not being as commercially successful, his career feels incredibly respectable. By building a foundation rather than celebrity, he helped raise a son who would go on to redefine poetic purity.

Their bond, which is rarely discussed but is very meaningful, keeps inspiring both viewers and artists. It serves as a reminder that mentoring can take many different shapes. Sometimes that creative legacy just manifests as presence rather than instruction. A transmission of sound. At the conclusion of a track is a trumpet. a name that is part of a middle name.